This post was meant to provide a brief glimpse into the festive activities of the people during the Middle Ages on Twelfth Night. However, like most of my blog posts, it wasn't as simple or quick as I initially thought. In doing my research, I turned up a lot of inconsistencies: Twelfth Night traditions have turned out to be quite slippery fish. Something done in the fourteenth century, for example, may have changed by the fifteenth. And so on. I don't wish to be like those writers who simply copy and paste others' work and hastily publish a post for fun. Unfortunately - or fortunately, I have an obsessive need to check details - and this, while it makes me a good researcher and writer, gives me headaches!!

First, let’s start with the straightforward stuff…

Throughout the English medieval year, there were many celebrations, but few could equal the bonkers madness that was Twelfth Night. Observed on January 5th, it marked the conclusion of the Twelve Days of Christmas, a period of sustained merrymaking and religious observance and owed much to the Roman festival of Saturnalia. Twelfth Night It was also known as the Eve of the Epiphany, and was the essence of medieval festivity, with both Christian symbolism and ancient customs melded together to create an occasion of conspicuous jollity and communal bonding.

So far, so simple.

Elements of the Celebration

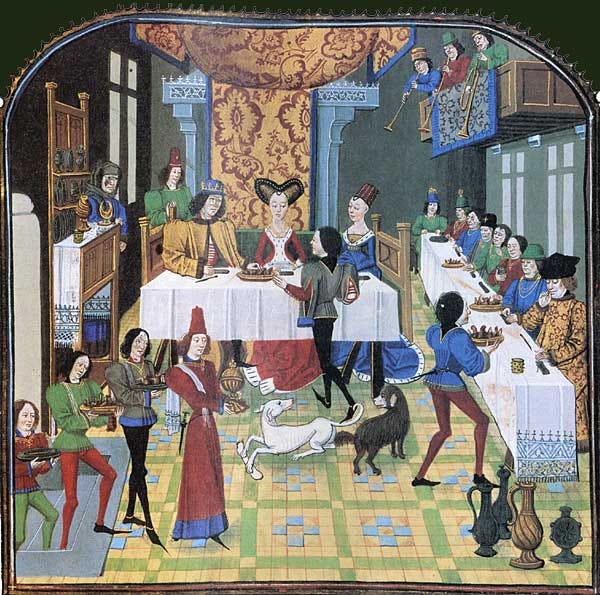

Central to Twelfth Night was the grand feast. For the noble class, this would have comprised many courses including a variety of meat and fish dishes, such as ornately decorated exotic birds such as swans and peacocks (although only for the highest classes), various sweet treats, and subtleties, fruit, cheese, and wafers. Even with financial constraints, those who were less fortunate prioritized having the best food they could afford. Again, none of this is in dispute. However, another element, often held up as being a pièce de résistance of the feast - the crowning of a Twelfth Night King (and sometimes Queen) or Bean King courtesy of finding a bean in a cake, is a little more problematic.

The Bean King/Twelfth Night King/Lord of Misrule

The popular version goes that a central feature of the feast was a special Twelfth Cake or King Cake, usually a rich, fruit-laden confection containing a hidden bean (sometimes a nut or tiny Jesus figurine). The person who found this token in their slice was declared either the “Bean King”, “King of Twelfth Night” or Lord of Misrule. In some cases, one half of the cake held a bean while the other half had a pea. While men ate one half and searched for the bean, women took pieces from the other half. The woman who found the pea became the “Queen of Twelfth Night”.

Traditionally, the “king” (we’ll leave the “queen” for now) was someone of a lower rank and was given carte blanche to rule over the festivities. He could cause as much mayhem as he pleased, embodying the temporary reversal of the usual social order. In fact, the alternative title of “Lord of Misrule” is far more accurately descriptive.

Here's where my problem lies. While it is often stated that this figure of chaos was elected on Twelfth Night and held power for only that night, I have encountered references where the 'Bean King' was selected on New Year's Day and may have overseen all Christmas festivities afterwards. This makes more sense. Perhaps this was an original approach, but it later shifted to the position being held for just one evening.

The best reference for the Bean King being chosen on New Year’s Day comes from the reign of Edward II. According to Kathryn Warner in her excellent blog, Edward II, the king spent New Year’s Day, or, the “day of the Circumcision of Our Lord” as the records have it, at Clipstone Lodge in Nottinghamshire. It is noted in the records that “Sir William de la Beche, a knight of the royal household, was the person lucky enough to find the bean that the cooks had added to the food, and therefore became Rex Fabae, King of the Bean, with the right to preside over the festivities. The length of his ‘reign’ is not clarified, but lasted until Twelfth Night.”1

A year later, a royal squire, Thomas de Weston, was the man who found the bean and assumed the title. Edward II rewarded both men with expensive silver gilt-ware for their services. It was most probably a tradition carried on from Edward’s forebears, and it certainly was still occurring in the reign of Edward III.2

Later references to Twelfth Night, in the Fifteenth Century, have the Bean Cake being eaten and the “Bean King”, “Twelfth Knight King” or “Lord of Misrule” transferred to this night. Certainly, by the sixteenth century, the poet Robert Herrick penned these lines describing how Twelfth Night was celebrated then:

TWELFTH NIGHT : OR, KING AND QUEEN.

by Robert Herrick

NOW, now the mirth comes

With the cake full of plums,

Where bean’s the king of the sport here;

Beside we must know,

The pea also

Must revel, as queen, in the court here.

Begin then to choose,

This night as ye use,

Who shall for the present delight here,

Be a king by the lot,

And who shall not

Be Twelfth-day queen for the night here.

Which known, let us make

Joy-sops with the cake;

And let not a man then be seen here,

Who unurg’d will not drink

To the base from the brink

A health to the king and queen here.

Next crown a bowl full

With gentle lamb’s wool:

Add sugar, nutmeg, and ginger,

With store of ale too;

And thus ye must do

To make the wassail a swinger.

Give then to the king

And queen wassailing:

And though with ale ye be whet here,

Yet part from hence

As free from offence

As when ye innocent met here.3

Entertainment

Alongside the feast, there was entertainment, with some acts taking place between courses. There was music from minstrels, juggling, and acrobatics. The participants would also have danced - maybe stately pavanes or more energetic estompies. The villagers also had their own music and dances, maybe not as sophisticated as the nobles', but equally enjoyable.

A big part of the Christmastide traditions, including the Twelfth Night revelries, was the use of masks and costumes. In particular, groups of players known as mummers, would dress up and perform traditional plays, often with the central theme being St George and the Dragon, a symbol of the triumph of the light over the dark. Among the poorer people, villagers or townspeople would themselves take on the roles.

Wassailing

Wassailing was an integral part of medieval Christmastide celebrations, and Twelfth Night in particular. The phrase Wassail comes from the Anglo-Saxon “waes hael” which translates as “good health”. The tradition differed from place to place, century to century, and class to class, but the basic intention was to give a blessing of health and good wishes for the days ahead.

The nobility and lords of the manor would fill a big wassail bowl with a drink made from mulled ale, honey, spices, apples, cream, and often an egg as well, for good measure. They would greet their friends, tenants, and servants with a “Waes Hael!” and the bowl would then be passed from person to person.

In the towns and countryside other traditions of wassailing developed. One of them involved groups of revellers travelling from house to house with the wassail bowl. The other, still practiced today in some areas, had groups of people wassailing orchards with a mulled cider. Trees were blessed so that they produced a bounty of fruit in the coming year. The wassailers also made lots of noise, banging pots and drums to both wake the trees and also to drive evil spirits away.

There were many different types of Twelfth Night celebrations. They seem to vary depending on location and period in history, but all have their roots in a pre-Christian past where it was important to bring light and mirth to the darkest days and to look forward to a successful year, especially where food production was concerned. These old traditions became entwined with Christian liturgical practices and both bumped along beside each other quite happily until later the later Puritan movement tried to stamp them out. The enduring popularity of many of these elements today is evidence of the need for fun and frolics in the heart of winter.

PostScript

Remember that saying that you have to have all of your decorations down by Twelfth Night or else you’d have bad luck for the year? Well, you can relax, as this is a relatively modern invention. Before Victorian times, when Christmas decorations were greenery - such as holly and ivy, it was supposed to be bad luck to take them down before Candlemas, on February 2nd. This was because it was believed that the semi-living decorations contained spirits who, if removed before the boughs had sufficiently wilted, would escape and cause mayhem around the house.4 The Victorians more or less reinvented Christmas, including having decorations made of paper or glass, so perhaps it was felt that it was more convenient to remove them after the main festivities had concluded. And so the new tradition (or superstition) of taking the baubles down on 5th or 6th January was born.

https://edwardthesecond.blogspot.com/2020/12/fourteenth-century-festive-traditions.html

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/members-area/members-magazine/2021/the-lord-of-misrule/

https://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/herrick/twelfthnight.htm

https://martinjohnes.com/2016/01/05/twelfth-night/

Extremely interesting!